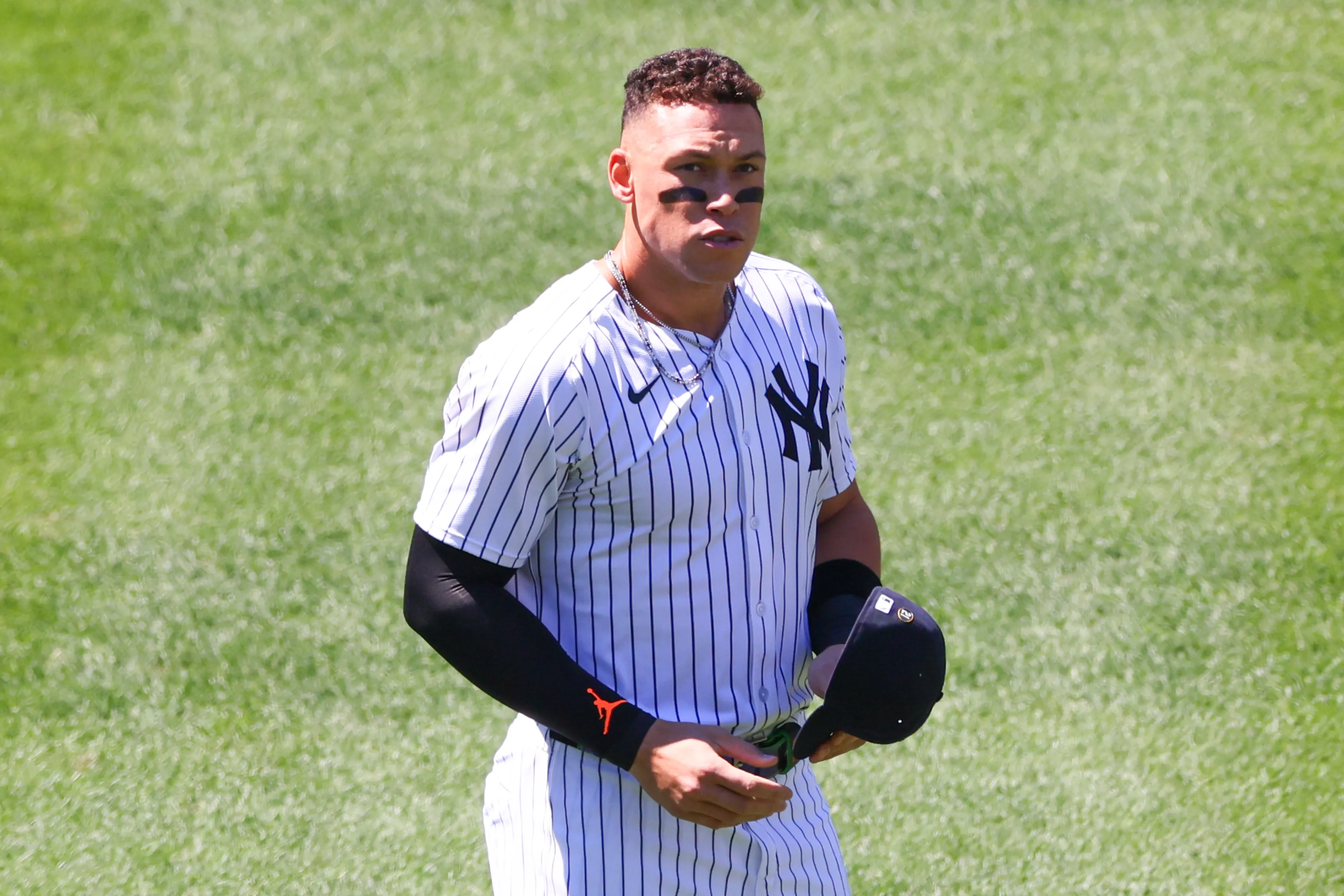

The Yankees Rushed Aaron Judge Back Too Soon — and the Whole Team Is Paying the Price

If you’ve watched the New York Yankees long enough, you know pennant races punish shortcuts. In early September 2025, the organization took one: they hustled Aaron Judge back into right field before he was truly ready to be Aaron Judge. The optics were heroic. The baseball was messy. And the costs—defensive, tactical, psychological—have rippled across the roster in ways a box score can’t capture.

A timeline the Yankees can’t spin away

On September 5–6, 2025, Aaron Judge returned to right field for the first time since a late-July flexor (forearm) strain. He was medically cleared, had been throwing in workouts, and publicly insisted he was ready to help.

| Aaron Judge: “I wouldn’t be out there if I wasn’t fine.”

Yet within those first games back, the eye test flashed yellow. There was a relay where he hit the cutoff man instead of unleashing the thunderbolt throw fans know by heart. There was a hesitant moment on a ball in the gap—a near-collision scenario involving Jazz Chisholm Jr.—that looked like the outfield version of tapping the brakes. None of it was disastrous. All of it was suggestive: this was a superstar managing his arm rather than trusting it.

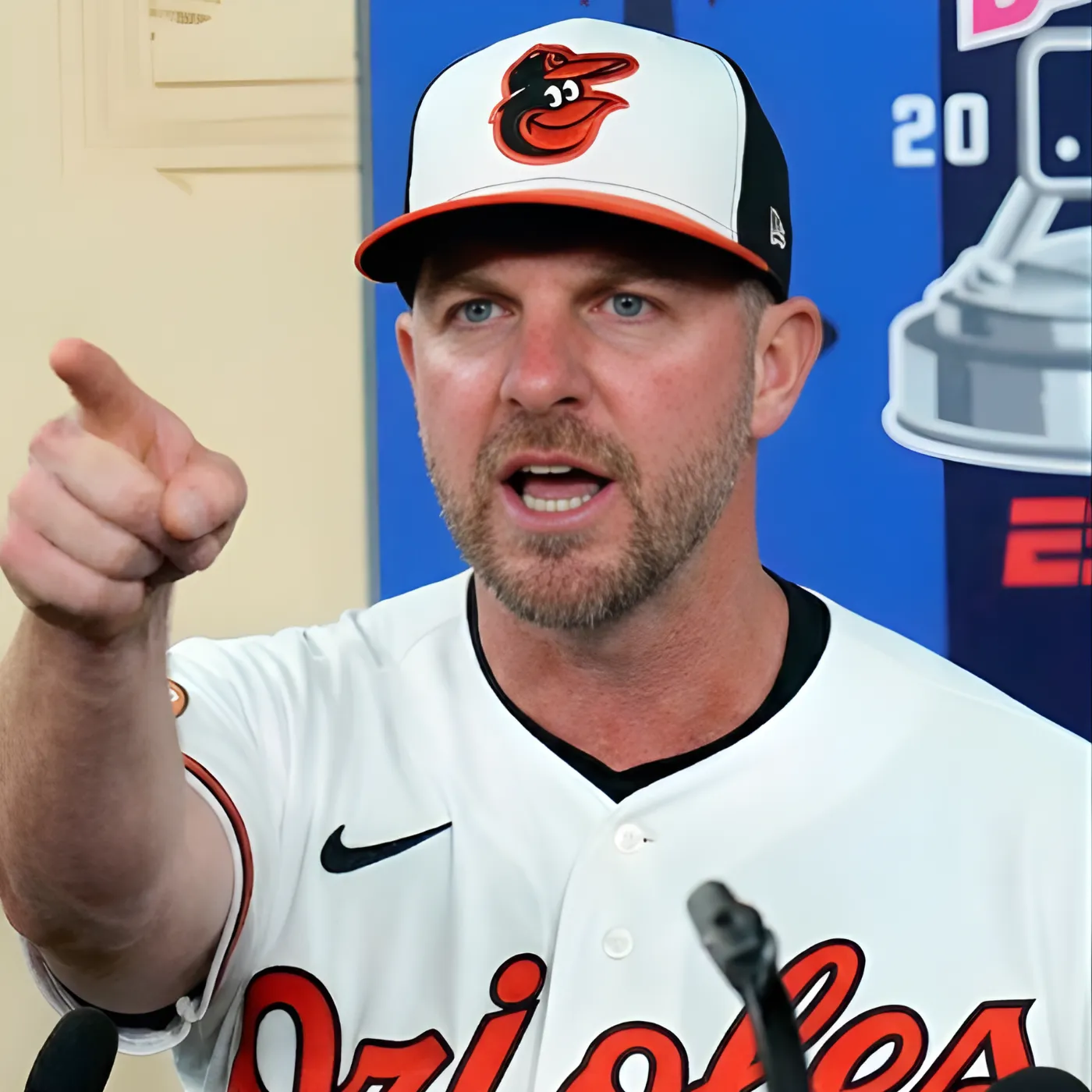

Before the return, manager Aaron Boone tried to temper expectations. He initially hinted that Judge might not throw like his pre-injury self for the remainder of the year, then walked it back, reframing the bar as “competent defense” rather than max-effort cannons from the warning track.

| Aaron Boone: “We just need him healthy enough to defend; it doesn’t have to be max velo.”

The Yankees also floated a measured usage plan: no outfield every day, and some defensive **rotation with Giancarlo Stanton to lighten Judge’s workload.

Clearing a doctor is not clearing the sport

One of baseball’s most persistent half-truths is that “cleared” equals “ready.” It doesn’t. You can be game-available without being role-optimal. Hitting form and throwing form don’t recover on identical timelines. A hitter may feel explosive in the box and still be 10–20% light on the kinetic chain that fuels his best throws—scapular rhythm, forearm tolerance, trunk-to-arm timing.

The distinction matters. “Available” Aaron Judge is an offensive force and a smart defender. “Peak” Aaron Judge is also a run-prevention weapon: he shuts down first-to-thirds with deterrent arm strength and flips run expectancy with a single throw. When that arm is dialed down—whether by design or discomfort—the geometry of right field changes, and so does the way opponents attack.

The defensive dominoes you could see from the bleachers

When Judge’s arm is 75–85% of max, everything shifts a few inches:

-

Outfielders play a step shallower to compensate for reduced carry, which invites balls over the head.

-

Cutoff men shade toward the line instead of the gap, opening seams elsewhere.

-

Third-base coaches, reading tape and body language, become more aggressive on borderline sends.

That near-miss with Jazz Chisholm Jr. captured the moment. Two elite athletes, both mindful of collision risk and both processing that one of them isn’t fully armed, took an extra beat. That beat is where triples live in September—and where a pitching staff loses the cushion it needs to live in the zone.

Mixed messages erode trust—inside and out

Public communication around injuries is never perfect, but consistency is a competitive advantage. The sequence—Boone says the arm might not be the same, then Judge counters that the manager hasn’t seen him throw recently, then the message gets softened—created the vibe of a compromise, not a plan.

| Aaron Judge: “He hasn’t really seen me throw lately.”

Inside a clubhouse, players read that. Opponents read that, too. Media amplifies it. The unintended takeaway: the Yankees were negotiating reality rather than owning a timeline. Successful returns have one voice: a clear role, a clear ramp, and a clear contingency if soreness flares. New York had three voices—medical, managerial, superstar—and not enough synthesis.

The Stanton rotation tax

On paper, rotating Giancarlo Stanton into the outfield to spell Judge is pragmatic. In practice, it shrinks late-inning flexibility. When Stanton plays defense, the bench must hold back a spot for potential pinch-running or defensive replacement scenarios. It complicates double-switch calculus, which in turn affects how aggressively the Yankees can play tight games. If New York had simply parked Judge at DH until his throws graded out at full trust, the nightly chessboard would be cleaner. Instead, the club is paying a small but compounding tax on alignment and substitutions.

September is a stress test, not a rehab lab

Every pitch in September has playoff consequences. That is precisely why teams can’t treat September as a live-fire rehab assignment. A right fielder operating at 80% may cost as many runs with his arm as he saves with his reads and routes. In tight races, one compromised throw can swing a series. The Yankees tried to split the difference—get the glove back on the grass while the arm caught up—and the standings rarely reward compromise.

The psychology of “I’m fine”

When Aaron Judge says he’s fine, he believes it. Elite athletes are wired to reinterpret pain as manageable information. But submaximal throwing isn’t a test of will; it’s a test of sequencing. A player can do 90% of tasks pain-free and still be vulnerable on the 10% that decide games. That’s why organizations are supposed to protect the player from his competitiveness—especially a captain who will always choose the team over the timeline.

| Aaron Judge: “I trust the work we’ve put in.”

Trust is an asset—until it tricks decision-makers into mistaking availability for readiness.

Opponents smell blood

Advance scouting is ruthless. The instant a superstar returns from an arm issue, every warm-up toss and relay arc is charted. Word spreads fast: “Test him early. Force a throw.” Even when runners are held, the message lands—you are on trial. That pressure multiplies the strain on footwork and angles, the exact places where tiny hesitations become extra bases. By putting Judge in right field before the arm fully passed its private checkpoints, the Yankees all but invited the exam.

What the numbers (would) say—even if you never see them

You don’t need proprietary biomechanics to see caution, but imagine the internal dashboard:

-

Average throw velocity: a few mph down from pre-injury baseline.

-

Release times: a hair slower on deep balls and relays.

-

Runner behavior: a tick more aggressive on first-to-third and tag-from-second decisions.

None of this turns Aaron Judge into a liability—he’s too smart and too skilled. But it narrows the margin where the Yankees usually create separation. Over 10–15 games, that narrowing becomes expected runs surrendered at the edges—the kind that change how your pitchers attack and how your manager scripts the seventh through ninth.

The hidden cost to the pitching staff

Pitching plans rely on conversion. When right field no longer deters extra bases, pitchers need different mixes to seek strikeouts instead of pitch-to-contact sequences. Counts lengthen. Stress pitches add up. A starter who should be at 84 through six might be at 95 through five because an inning extended on an aggressive send the defense couldn’t challenge. The bullpen, already volatile in any given series, absorbs earlier-than-ideal exposure. These are compound-interest problems, and the interest rate spikes when your best outfield arm is living at “good enough.”

The clubhouse calculation

Teammates won’t say it on the record, but they know when a guy is grinding at less than full capacity. They respect it. They also recalibrate around it. Middle infielders change cutoff landmarks. Catchers set up for tags assuming a short-hop. Coaches rehearse communication priorities on tweener balls. None of this is panic; it’s adaptation. But every adaptation is a concession to the reality that the defender in right isn’t the apex version of Aaron Judge. Multiply concessions, and you get a defense that’s good instead of suffocating.

August mattered—and so did the impatience

To be fair, this impatience has a human core. In August, Aaron Judge began light throwing, played catch with Giancarlo Stanton, and reported he felt “good”—with a little soreness on the edges. For a captain wired like Judge, watching from the DH slot is like running with a parachute. He wanted the full job back.

| Aaron Judge: “The waiting is the hardest part.”

That’s exactly when leadership has to be stronger than the moment. Patience isn’t timidity; it’s strategy. Buying one more week of throws at full intent can save three weeks of compromised defense in the games that matter most.

Process over panic: the road not taken

What would the best-practice plan have looked like?

-

Keep Aaron Judge at DH only until he logs three consecutive throwing sessions at target velocity and accuracy with no next-day setbacks.

-

Run one live, competitive simulation of tag plays with the third-base coach sending aggressive runners.

-

Announce a public ramp: one outfield start every third day for a week, then every other day, then daily—if the metrics and the arm match the eye test.

No spin. No mixed cues. Just a transparent ramp that values October over optics.

Lessons the Yankees must lock in

-

Medical clearance is the floor, not the finish line. It green-lights participation, not peak role execution.

-

September urgency is not a license to bend timelines. The standings punish half measures.

-

One voice matters. Align medical, managerial, and player messaging before the microphones turn on.

-

Protect competitors from themselves. Stars always say yes. Leaders set the terms of that yes.

These aren’t abstractions. They’re edge management—the small, boring disciplines that separate clubs built to win a week from clubs built to win a month.

Why the cost is bigger than one weekend in September

This debate isn’t about a single relay or one near-miss in the gap. It’s about how a contender converts adversity into advantage. Opponents know the quickest way to wobble the Yankees is to bait them into reactive decision-making—responding to today’s headlines instead of executing a pre-committed plan. By rushing Aaron Judge back to the grass before he was fully armed, New York reacted. The price came due on the bases, in the bullpen, in the lineup flexibility, and in the public narrative that now frames every throw as a referendum.

What needs to happen now

The beauty of baseball is that you can still course-correct.

-

Give Judge a published ramp: two to three DH days between outfield starts until the throw metrics say “go.”

-

Make the throwing progression independent of game outcomes. Don’t accelerate just because the club loses a tight one.

-

Empower the fourth outfielder with defined starts so the defense doesn’t feel like a patchwork quilt by series’ end.

-

Communicate honestly. If the arm is at 85% today, say it. Fans can handle truth; they revolt at spin.

Above all, resist the urge to prove anything. Aaron Judge doesn’t need to prove toughness. The Yankees need to prove process.

The verdict

The Yankees weren’t reckless because they ignored doctors; they were reckless because they confused clearance with completion and urgency with strategy. They asked a still-recovering superstar to do superhero things and then acted surprised when the cape didn’t flutter the same. In the process, they stressed the pitching plan, narrowed tactical options, and invited opponents to probe the exact seam that wasn’t yet stitched.

None of this is irreparable. All of it was avoidable.

Two weeks from now, the story can sound very different if the club tightens its process and protects its cornerstone. Until then, the takeaway is blunt: rushing Aaron Judge back to right field before his arm could be its old self didn’t just put one player at risk—it put the Yankees’ run-prevention engine on a diet at the exact moment it needed calories.

The Yankees tried to split the difference between urgency and health—and ended up compromising both. Bring Aaron Judge back to right field when his throws match his instincts, not when the calendar says it’s time.

Related News